The Meat Dilemma: Ideology vs. Evidence

Ellen White in 1864.

A Religious Awakening

Fuzzy vision fading to black, Ellen Gould Harmon White collapsed to the dirt floor of her Portland, Maine church in 1847. Seizures were not unusual for Ellen, the result of a traumatic brain injury at age nine when a rock struck her face. Today, this would likely be diagnosed as epilepsy, but Ellen believed these episodes were divine messages. Her visions laid the foundation for the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) Church, now the world’s 12th largest religion. Central to her teachings was the belief that a meatless diet brought spiritual purity and closeness to God.

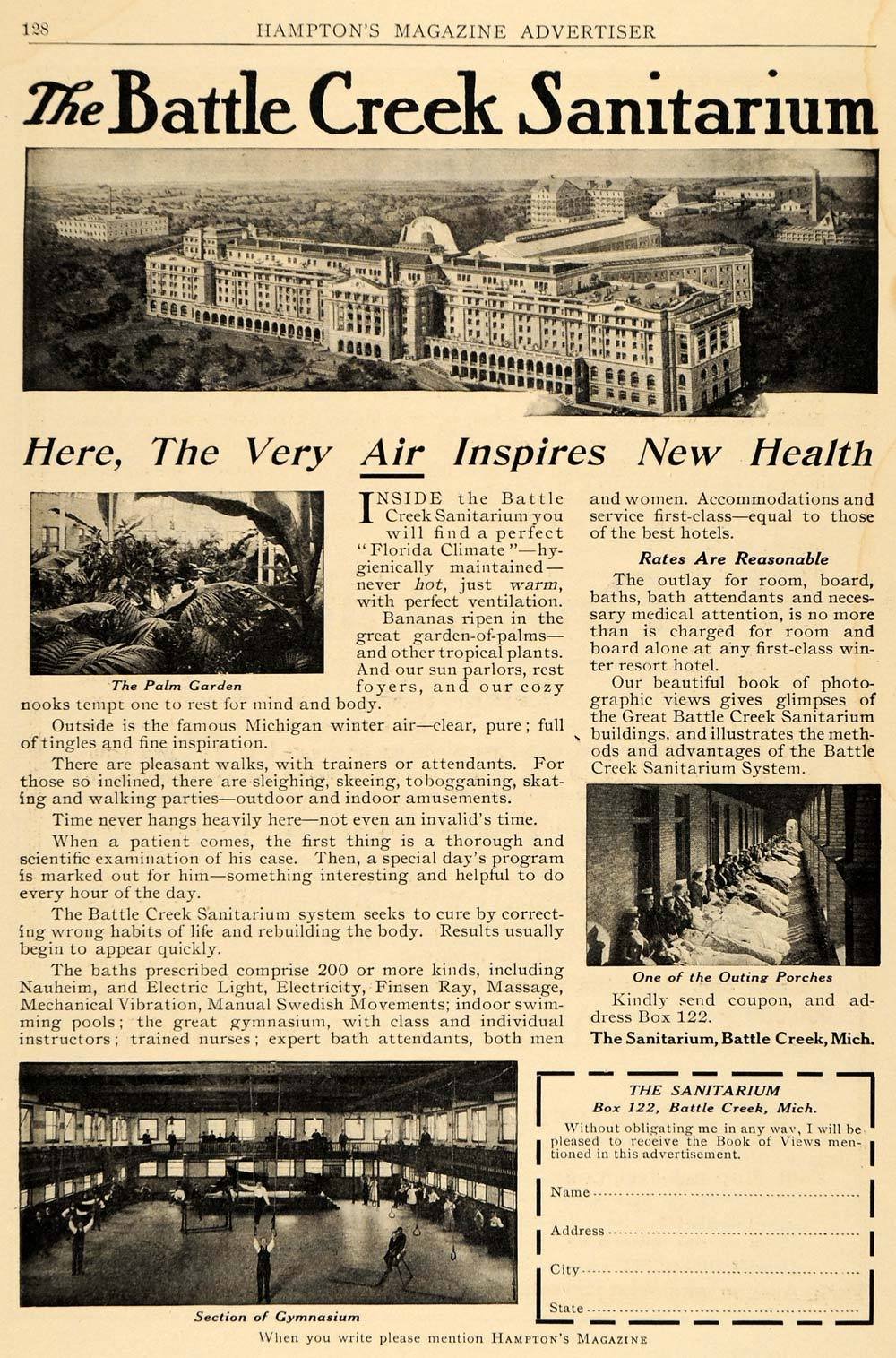

In 1855, as the Adventist movement gained traction, Ellen and her husband relocated to Battle Creek, Michigan, at the urging of four church members. Among them was the family of a frail, timid boy named John Harvey Kellogg. Initially hired as a printer's apprentice for Ellen’s religious publications, Kellogg became deeply devoted to SDA teachings and later trained as a physician to promote its principles through medicine. Returning to Battle Creek in 1875, he established the Battle Creek Sanitarium, blending medical treatment with religious ideology.

John Harvey Kellogg

Kellogg’s dietary practices were as extreme as his medical treatments. He believed a bland, vegetarian diet could suppress carnal desires, particularly masturbation, which he called a "solitary vice." His experimental meals included a concoction of baked oatmeal and cornmeal biscuits, ground into tiny pieces—a prototype of modern granola. His brother, Will Kellogg, later added milk to this mixture, creating the first breakfast cereal. These early experiments would spark a rivalry with C.W. Post, a former sanitarium patient, and pave the way for the industrial food revolution.

Yet Kellogg’s ideology extended far beyond diet. He pioneered invasive "cures" designed to curb sexual impulses, including circumcising boys without anesthesia and using acid treatments on girls. His beliefs about purity also led to eugenics advocacy, culminating in the founding of the Race Betterment Foundation in 1906. Working with Michigan’s Board of Health, he championed sterilization laws targeting those he deemed "unfit," leaving a dark legacy of medical abuses.

Kellogg’s vision of diet, rooted in religious doctrine, was not simply about health—it was about control. His contributions to American breakfast culture and dietary norms are inseparable from the Adventist ideology that shaped them, raising questions about how religious beliefs can infiltrate science and public health.

While Kellogg was one of the SDA church’s most prominent and devout proponents, Ellen White and the church leadership broadened their influence beyond a single figure. The Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) church strategically worked to promote their meatless diet and health ideologies through an extensive network of institutions. Over time, they built 198 sanitariums across the United States, along with medical colleges to train doctors in their dietary and health practices. In 1917, the church founded the American Dietetic Association (now the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics) to formally educate dietitians in their vegetarian principles, originally intended to foster chastity and purity. Today, the Academy describes itself as “the world’s largest organization of food and nutrition professionals... shaping the public’s food choices.”

The church’s mission to advance vegetarianism also extended to establishing educational and food production enterprises. According to a paper titled The Global Influence of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church on Diet, the church has “established hundreds of hospitals, colleges, and secondary schools and tens of thousands of churches around the world, all promoting a vegetarian diet.” Key institutions include Loma Linda University, the Sanitarium Food Company, and Loma Linda Foods.

Over the past century, Loma Linda University has trained thousands of doctors, nutritionists, dietitians, and researchers, amplifying the SDA church’s dietary ideology. The university has sponsored and funded hundreds of studies on plant-based diets, making it difficult to find major positive findings on vegetarianism or veganism in nutritional science untouched by SDA influence. The SoyInfo Center underscores this reach, noting that “no other organization or group of people has played a more important role than Seventh-day Adventists in introducing soyfoods, vegetarianism, meat alternatives, wheat gluten, dietary fiber, or peanut butter to the Western world.”

A 1910 advertisement for the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

A physical-fitness class at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, ca. 1890s. Director John Harvey Kellogg saw outdoor exercise, particularly in cold weather, as fundamental to health. Image from the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library.

The Religious Roots of Vegetarianism

Rev. Sylvestor Graham and his famous Graham Crackers.

The rise of vegetarianism in America during the 19th and early 20th centuries did not occur in isolation. It was deeply intertwined with the broader temperance movement, which was influenced by religious theology linking health to morality. Temperance advocates championed abstinence from alcohol and often from meat, believing that such choices aligned with moral purity and physical well-being. Among the movement’s most prominent figures was Reverend Sylvester Graham, though his influence paled in comparison to Ellen White and the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Graham, best known today as the namesake of Graham crackers, was inspired by the Treatise on Physiology by French physician François-Joseph-Victor Broussais, published in 1826. Broussais argued that dietary choices profoundly affect health, a concept that Graham adapted through his religious lens. Convinced that Adam and Eve had subsisted solely on plants in the Garden of Eden, Graham advocated for a vegetarian diet. His followers, practicing what came to be known as “Grahamism,” popularized Graham flour, Graham bread, and the now-famous Graham crackers. Graham’s ideas later heavily influenced Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, as both men believed that a meatless diet could prevent “impure thoughts” and reduce the risk of masturbation.

In 1850, Graham co-founded the American Vegetarian Society in New York City, which published a journal that continues today as The Vegetarian. Graham died at the age of 57 while undergoing a controversial treatment involving an opium enema. Some historians, such as Stephen Nissenbaum, suggest that his death followed a lapse in his dietary principles, as he reportedly consumed liquor and meat in a desperate attempt to regain his health.

The modern term “vegan” originated much later, coined in 1944 by British woodworker and animal rights activist Donald Watson. Watson, a member of the British Vegetarian Society, sought to differentiate veganism from vegetarianism after tuberculosis infected 40% of the United Kingdom’s dairy cows. Concerned about the spread of disease, Watson advocated for the exclusion of dairy and eggs alongside meat. He introduced the term “vegan,” though he initially had to clarify its pronunciation after many in Britain referred to it as “veejan.” Over time, the term and the lifestyle gained traction.

Historically, meatless diets have often been shaped by religious, moral, or ideological beliefs rather than purely practical or nutritional considerations. One of the earliest recorded vegetarian traditions comes from ancient India, where Jainism (traditionally known as Jain Dharma) promoted non-violence, or ahimsa, as a core principle, extending to the treatment of animals. Similarly, during the Christianization of the Roman Empire, monks avoided meat for ascetic reasons tied to purity and abstinence. Other examples include Chinese Buddhism and Taoism, which prescribed egg-free vegetarian diets for monks, and Vedic Hinduism, where the Manusmriti law book extolled the spiritual rewards of abstaining from meat.

Despite these religious and moral origins, vegetarianism underwent a cultural transformation in America during the 20th century. While meat consumption in the West rose dramatically between 1900 and 1960 due to advancements in transportation and refrigeration (pioneered by figures like Clarence Birdseye), the 1970s saw a countercultural resurgence of meatless eating. How did a diet rooted in religious ideals become associated with hippies, hipsters, and New Age radicals? The answer lies in shifting cultural values and the blending of ideology with lifestyle trends.

The Rise of Modern Plant-Based Ideology

In 1971, Frances Moore Lappé published Diet for a Small Planet, a book that examined global hunger through the lens of food production inefficiencies. Lappé, who had recently left UC Berkeley, argued that a grain-based diet could theoretically eliminate world hunger by reallocating resources away from meat production. Her focus was on critiquing the industrial food system rather than improving individual health. Nonetheless, the book gained significant attention and helped popularize the idea of plant-based diets as a potential solution to environmental and social issues. Lappé’s work remains influential, and she continues to speak publicly about the connections between diet and global sustainability.

Around the same time, Australian ethics professor Peter Singer published Animal Liberation. Singer’s work provided the first modern, scholarly argument against eating meat on moral grounds. Though philosophical opposition to meat consumption dates back to ancient Greeks and Hindus, Animal Liberation galvanized the contemporary animal rights movement. With support from organizations like PETA, which distributed free copies of the book, Singer’s arguments reached a global audience. Michael Pollan later described Animal Liberation as a rare book that demands readers “either defend the way you live or change it.”

By blending the health-centric ideology of groups like the Seventh-day Adventist Church with a secular, ethical framework that positioned veganism as better for the planet, the movement gained significant traction. The counterculture of the 1970s viewed meatless diets as a form of anti-establishment protest. If industrialized food represented “the establishment,” then vegetarianism and veganism became tools for enacting social change. Communes like The Farm in Tennessee, founded by a group of San Francisco hippies, began promoting soy-based, meatless recipes and ideals. Progressive Adventists likely saw these developments as a validation of their teachings, particularly as Loma Linda University studies were increasingly cited in academic papers.

By 1975, vegetarianism had captured mainstream attention. The New York Times published a headline, “Vegetarianism: Growing Way of Life, Especially Among the Young,” explicitly linking Lappé’s environmental arguments with studies conducted at Loma Linda University. With public interest growing, the movement sought validation from the medical community to solidify its position.

Their breakthrough came in the 1980s, notably through the work of Dr. John McDougall. A stroke at age 18 had inspired McDougall to pursue medicine, eventually leading him to blame his early health issues on his diet of “eggs, double-cheese pizzas, and hot dogs.” He hypothesized that a strictly vegan diet could prevent or cure chronic diseases. In 1986, the Seventh-day Adventist Church invited McDougall to run the “McDougall Program” at their St. Helena Hospital in Napa Valley. While McDougall was not an Adventist, his work aligned with the church’s mission, and they extensively promoted his program.

Anti-Meat Investing

John Wesley preaching in Aldersgate, London (May, 1738).

The mid-to-late 1990s saw a surge in “socially responsible investing” (SRI), an approach that aligns investments with ethical or moral values. Interestingly, the roots of SRI are religious. In the 1700s, John Wesley, founder of the Methodist movement, urged his followers to avoid partnerships with those profiting from alcohol, tobacco, weapons, or gambling (often referred to as "sin stocks"). Similarly, Islamic finance has long prohibited investments in industries inconsistent with Shariah law.

In the late 1990s, the growing awareness of environmental concerns, particularly climate change, led SRI to focus on environmentally sustainable investments. This shift was guided by Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) criteria, with additional direction from the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). What made this wave of SRI unique was a generation shaped by the counterculture of the 1970s—now with significant wealth—seeking investments that aligned with their values.

In 2006, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) published a report titled Livestock’s Long Shadow, which made headlines with the claim that livestock production was responsible for over 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions—more than all transportation emissions combined. However, this conclusion was challenged by Frank Mitloehner, Ph.D., an animal scientist at UC Davis, who identified critical flaws in the methodology. The report’s lead author, Henning Steinfeld, later clarified that it had compared direct emissions from transportation to a full life-cycle analysis of livestock, which included factors like feed production, fertilizer, and land conversion. By contrast, transportation emissions were measured solely by exhaust, excluding manufacturing, assembly, and road maintenance. The study also failed to distinguish between regenerative farming practices and large-scale industrial livestock operations, further skewing the results against the meat industry.

Despite Steinfeld’s corrections, the report's initial conclusions left a lasting impact. It spurred unprecedented investment in plant-based food companies, fueled by a moral narrative that tied dietary choices to planetary health. Companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Burger emerged, creating competition for longstanding players like Loma Linda Foods. For the first time, the meat alternative market featured proprietary, patented products with significant investment appeal.

Major investors, including family offices heavily backing plant-based food ventures, began funding documentaries, books, and other media to promote these diets. Their intention, much like that of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, likely stemmed from a genuine desire to contribute positively to the world. They believed that promoting plant-based diets would benefit both people and the planet.

Finally, in May 2020, the New York Times published an opinion piece by Jonathan Safran Foer titled “The End of Meat is Here,” boldly declaring that the time had come to abandon meat consumption entirely. However, this perspective has been met with strong opposition from numerous scientists, medical professionals, researchers, dietitians, and nutritionists who challenge its conclusions.

The Evolutionary Case for Meat

Figure 5. from Meat and Nicotinamide: A Causal Role in Human Evolution, History, and Demographics

Steady rise of meat/nicotinamide in surviving hominids until the Neanderthals. Homo sapiens survived, but only just, and then we subjected ourselves to large meat variances with demographic consequences.

Meat has long been a cornerstone of the human diet, shaping our evolution in profound ways. Archaeological and paleoanthropological evidence suggests that as early as 3 million years ago, early hominids began increasing their meat consumption. This dietary shift coincided with the development of greater brain capacity, enabling the creation of stone tools and fostering the physical adaptations necessary for foraging and hunting. Often referred to as the "cradle of mankind," the Rift Valley in East Africa was the site of these evolutionary leaps. In this predator-rich environment, the ability to hunt and forage intelligently was a critical survival advantage.

The transition from prey to predator required not only physical tools but also advanced social and cognitive skills. Early hominids began crafting tools for hunting, butchering, and cooking, processes that reduced the energy demands of chewing and digestion. The cooperative nature of hunting and food sharing further catalyzed the development of social and altruistic behaviors, strengthening group cohesion and success. These innovations fueled the growth of large, energy-intensive brains. Notably, during early development, up to 90% of a child's basal metabolic rate is devoted to brain growth—a process that would have been impossible without nutrient-dense animal-derived foods.

Professor Robert Pickard, Emeritus Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Cardiff, who sits on the Meat Advisory Panel (MAP), underscores the importance of meat for brain development:

“This is because red meat is an excellent source of energy – although the brain is just two per cent of our body weight, it uses about 20 per cent of our energy intake. Red meat from grass-fed cattle is also a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, including a type of long-chain Omega-3 unsaturated fat called DHA which is vital for brain development. There are two active forms of long-chain Omega-3s in the body, EPA and DHA. DHA is the most abundant Omega-3 fatty acid in the brain and low levels of DHA can adversely affect various aspects of cognitive function and mental health, especially in young people and children.”

Throughout human history, dietary composition has consistently been linked to major turning points in our evolutionary and societal development. Meat, in particular, has played a pivotal role, reducing digestive costs and optimizing nutritional input. Societies have often thrived on meat-centric diets, while periods of scarcity or dietary shifts away from meat have frequently been associated with societal decline.

Cultures That Thrived on Meat

Inuit children eating raw caribou.

The Inuits

At the turn of the 20th century, while Kellogg was promoting his meatless diet in Battle Creek, a Harvard-trained anthropologist named Vilhjalmur Stefansson was living with Inuit tribes in the Arctic, documenting their diet and lifestyle. The Inuits’ diet consisted almost entirely of caribou, salmon, and eggs, with little to no plant-based foods. Stefansson observed that they were among the healthiest people he had ever encountered, exhibiting no signs of chronic disease. Contrary to contemporary dietary beliefs, the Inuits considered the fattiest parts of meat to be the most nutritious.

Intrigued by these findings, Stefansson and a colleague undertook a year-long experiment, adhering strictly to a meat-only diet. They found that they felt healthiest when consuming the fattiest cuts of meat and organ meats like brains. At the conclusion of their experiment, a committee of scientists conducted thorough health assessments and found no negative health outcomes in either participant. Stefansson’s work remains one of the most rigorously controlled investigations into meat-based diets in history.

The Masai and Samburu of Kenya

In the 1960s, George Mann, a professor of biochemistry, began studying the Masai people in Kenya. The Masai diet consisted exclusively of milk, blood, and meat, with vegetable crops reserved for feeding livestock. Mann’s research revealed that the Masai exhibited no signs of chronic illnesses common in the West, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, or cancer. Mann’s findings were corroborated by studies of the Samburu tribe in Northern Kenya, who followed a similar diet with equally remarkable health outcomes.

The Native American Tribes

Between 1898 and 1905, physician and anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička studied Native American tribes in the Southwest, focusing on their predominantly meat-based diet, which relied heavily on buffalo. In his comprehensive report for the Smithsonian Institution, Hrdlička noted that these tribes exhibited exceptional health and longevity, with one of the highest percentages of centenarians ever recorded—40 times higher than in Western cultures of the same era. He observed an absence of malignant diseases, stating that if such conditions existed, they were “extremely rare.”

The Mongols

The Mongolian Army, founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, is renowned for conquering vast territories across Europe and Asia, amassing nearly 12 million square miles of land. The nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols necessitated a diet based almost entirely on dairy products from their herds of goats, sheep, oxen, camels, and yaks. One of their staple drinks, kumis, was made by fermenting milk in large leather bags. Fueled primarily by animal products, the Mongolian Army became legendary for their speed, strength, and agility, earning a reputation as some of history’s most formidable warriors.

Meatless Societal Collapse

The Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange refers to the widespread transfer of diseases, ideas, food, and populations between the “New World” and the “Old World” following Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Americas in 1492. The introduction of new diseases devastated Native American populations, with some scholars suggesting that tribes subsisting on low-meat, high-maize diets were particularly vulnerable due to preexisting nutritional deficiencies. Similarly, historians have posited that the collapse of the ancient Mayan civilization may have been exacerbated by their dependence on maize as a dietary staple.

The consequences of maize dependency extended beyond the Americas. When maize was introduced to Europe, it became a staple in poorer communities in Spain and Italy, where meat was scarce. This dietary shift led to outbreaks of pellagra—a disease caused by niacin (vitamin B3) deficiency—which disproportionately affected populations relying on maize as their primary food source.

Easter Island

Easter Island offers a striking case study of the consequences of a meat-deficient diet in a geographically isolated population. With no large game on the island, the inhabitants eventually resorted to eating rats and competing for seagull eggs to meet their nutritional needs. This lack of substantial protein sources contributed to severe resource scarcity and eventually led to societal collapse. The island’s history serves as a stark example of how the absence of reliable meat sources can destabilize a population.

Ireland

The Irish Potato Famine of the mid-19th century highlights the dangers of an overreliance on low-meat, high-starch diets. Anthropological research from the University of Birmingham supports a broader pattern, noting that “high meat intake correlates with moderate fertility, high intelligence, good health, and longevity with consequent population stability, whereas low meat/high cereal intake correlates with high fertility, disease, and population booms and busts.” In Ireland, a dependence on potatoes left the population vulnerable to malnutrition, disease, and eventual collapse when potato crops failed. The famine was catastrophic, demonstrating the fragility of populations that lack sufficient access to nutrient-dense meat.

Animal Protein vs. Plant Protein

Protein is a critical macronutrient composed of amino acids, often referred to as the building blocks of life. It plays a vital role in essential bodily functions, including muscle and tissue repair, hormone regulation, enzymatic activity, and the transportation and storage of molecules such as oxygen. Both animal and plant-based foods provide protein, though the quality and amino acid composition can vary significantly between sources.

PDCAAS-adjusted P/E ratios of animal and plant food sources and diets

A protein source is classified as complete if it contains all nine essential amino acids—namely isoleucine, histidine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. In contrast, incomplete proteins are missing one or more of these amino acids. Animal proteins, such as those found in eggs, milk, meat, fish, and poultry, are complete and rank highest in quality based on the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS), the most widely used metric for assessing protein quality in nutritional research.

Without sufficient dietary protein, the body begins breaking down its own muscle and tissue to meet protein needs. The current Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for protein, as outlined in U.S. Dietary Guidelines, is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight. However, this figure represents the minimum amount required to prevent muscle loss, not the optimal intake for health or performance. For example, an individual weighing 165 pounds (75 kilograms) would need a minimum of 60 grams of high-quality protein daily to maintain muscle mass. For context, a 6-ounce steak provides approximately 42 grams of complete protein.

The RDA is calculated based on healthy adults engaging in minimal physical activity, but this baseline recommendation does not reflect variations in individual needs. Factors such as age, weight, height, and physical activity levels all influence protein requirements. Research suggests that optimal protein intake varies as follows:

Minimal physical activity: 1.0 grams per kilogram of body weight per day

Moderate physical activity: 1.3 grams per kilogram of body weight per day

Intense physical activity: 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day

Additional functional needs should also be considered, such as support for spermatogenesis, fetal development, immune response, blood circulation, and skeletal muscle health. Children and infants, experiencing rapid growth, as well as older adults combating age-related muscle loss, require even higher protein intakes to meet their physiological demands.

Infographic created by Diana Rodgers RD.

For a healthy, active 165-pound (75-kilogram) male, protein needs can be substantially higher than the standard RDA suggests. Research indicates such an individual may require approximately 120 grams of protein per day to support muscle maintenance and overall health. Importantly, this estimate assumes all protein consumed comes from high-quality, complete protein sources that provide all essential amino acids.

To meet this requirement with animal-based sources, it would take roughly three 6-ounce steaks per day, providing complete protein profiles along with essential micronutrients. However, meeting this need through plant-based proteins alone presents significant challenges. Since all plant proteins are incomplete sources, careful planning and increased food intake are necessary to achieve both the necessary protein quantity and a complete amino acid profile.

For example, obtaining 120 grams of protein solely from broccoli would require consuming approximately 120 ounces (more than 46 cups). Even then, this approach would fail to supply three essential amino acids: isoleucine, leucine, and methionine. A similar analysis by registered dietitian Diana Rodgers compared the protein value of a 4-ounce steak with that of kidney beans, a commonly cited plant protein source. To match the steak’s protein content, one would need to eat 12 ounces of kidney beans combined with a cup of rice, amounting to roughly 638 calories and 122 grams of carbohydrates—still falling short in other vitamins and minerals.

In addition to being the most complete protein source, red meat offers unparalleled nutrient density. It provides the most bioavailable form of heme iron, addressing what remains the world’s most common nutritional deficiency. Meat is also a critical source of vitamin B12 (cobalamin), a nutrient with significantly higher deficiency rates among those on meatless diets. Remarkably, just 3 ounces of red meat delivers more than half the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for selenium and niacin, as well as nearly half the RDA for zinc, further emphasizing its nutrient-rich profile. Micronutrient contributions from various meats, including beef, lamb, pork, venison, and calf liver, underscore their unparalleled value in a balanced diet.

Table 1. from The role of red meat in the diet: nutrition and health benefits

Selected micronutrients in meats related to nutrition claims classification. Data from McCance and Widdowson's Composition of Food ND, no data; Beef, beef average, trimmed lean, raw; Lamb, lamb, average, trimmed lean, raw; Pork, pork, trimmed lean, raw; Venison, venison, raw; Calf liver, liver, calf, raw.

The consumption of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFAs)—namely eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)—is crucial for various health benefits. These include supporting fetal development, promoting cardiovascular health, and enhancing brain function, with notable associations in reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Dietary sources significantly influence omega-3 levels in the body, with distinct differences observed between omnivores, vegetarians, and vegans. A 2005 British cross-sectional study highlights these differences (see Table 2 in the study for a full chart):

EPA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 0.72 / Vegetarians: 0.52 / Vegans: 0.34

DPA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 0.81 / Vegetarians: 0.76 / Vegans: 0.72

DHA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 1.69 / Vegetarians: 1.16 / Vegans: 0.7

These findings demonstrate that omnivores tend to maintain higher levels of these critical omega-3 fatty acids. The difference largely stems from the inefficiency with which vegans and vegetarians convert alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), found in plant-based sources like flaxseeds and walnuts, into EPA and DHA. This conversion process is inherently limited in humans, further complicating efforts to achieve sufficient omega-3 levels on plant-based diets.

Importantly, these results do not imply that obtaining adequate omega-3s is impossible on a vegan or vegetarian diet, but rather that it is more complex. Supplementing with algae-based DHA or consuming fortified foods may help address these gaps, but including animal products in one’s diet offers a natural and efficient means of maintaining optimal levels. These findings have been corroborated in studies of Austrian, Dutch, Australian, Finnish, Chinese, and U.S. populations, reinforcing the nutritional advantages of animal-derived omega-3 sources.

An adapted diagram from Essential fatty acids: biochemistry, physiology and pathology (Adapted by Chris Kresser, M.S., L.Ac)

Clinical Benefits & Risks Related to Meat

Dietary studies present significant challenges due to the numerous confounding variables at play. Individuals vary widely in their genetics, cooking methods, food sources, ingredient choices, light exposure, medications, pre-existing conditions, geographic locations, socioeconomic advantages, access to healthcare, levels of physical activity, and more. These factors make it difficult to determine whether changes in disease risk or development can be attributed to a single ingredient in someone’s diet.

Additionally, the type of meat consumed—whether processed or unprocessed, grass-fed or grain-fed—can significantly influence its nutritional composition. Unfortunately, many nutritional studies fail to adequately control for these variables, further complicating the interpretation of their findings.

One of the most significant challenges in observational studies on meat is the “healthy-user bias.” This bias arises because individuals who avoid meat, often due to its negative reputation over the past 40 years, are more likely to engage in other health-conscious behaviors, such as exercising regularly, sourcing high-quality foods, or maintaining balanced diets. Conversely, regular meat consumers may be less likely to engage in these same behaviors, making it difficult to isolate the effects of meat consumption itself.

Despite these challenges, there is a body of evidence that has attempted to control for these confounding factors, providing insights into the potential clinical benefits and risks associated with meat consumption:

Depression & Anxiety

Red meat, as a nutrient-dense source of vitamins and minerals, may play a protective role in preventing common mental health disorders. Research in nutritional psychiatry has highlighted that women consuming either less or more than the recommended intake of red meat were significantly more likely to develop clinical depression, mood disorders, or anxiety.

Felice Jacka, Ph.D., an associate professor at Deakin University’s Barwon Psychiatric Research Unit, emphasized the importance of red meat for brain health:

“We had originally thought that red meat might not be good for mental health, as studies from other countries had found red meat consumption to be associated with physical health risks, but it turns out that it actually may be quite important…

When we looked at women consuming less than the recommended amount of red meat in our study, we found that they were twice as likely to have a diagnosed depressive or anxiety disorder as those consuming the recommended amount.

Even when we took into account the overall healthiness of the women’s diets, as well as other factors such as their socioeconomic status, physical activity levels, smoking, weight and age, the relationship between low red meat intake and mental health remained. Interestingly, there was no relationship between other forms of protein, such as chicken, pork, fish or plant-based proteins, and mental health.”

Theses findings were replicated in a prospective study of 10,094 Spanish individuals enrolled in the SUN Project, in which researchers also observed that a lack of meat in the participant’s diet led to an increased risk of depression. Conversely, other research has shown that vegetarians are much more likely to experience depressive symptoms, which was further confirmed in a large 2018 cohort study of 90,380 participants.

Multiple Sclerosis

In 2019, researchers explored the connection between red meat consumption and the risk of developing first clinical demyelinating events (FCD), a condition that often precedes a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS). After adjusting for potential confounding factors—including history of infectious mononucleosis, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (vitamin D3) levels, smoking status, race, education, body mass index, and dietary misreporting—they found a notable protective association. Specifically, higher consumption of unprocessed red meat was linked to a 19% reduction in the risk of FCD per one standard deviation increase in red meat intake.

The researchers highlighted that red meat is a significant source of very long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (VLCn3PUFA) and vitamin D, both of which are critical for central nervous system health. Deficiencies in these nutrients have been implicated in increased risk and progression of MS, underscoring the potential protective role of red meat in this context.

Neurodegernative Disorders

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the relationship between meat consumption and cognitive function, as well as the risk of cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia. The analysis included 29 studies with highly inconsistent findings. While the majority of studies reported no significant association between meat intake and cognitive disorders, a meta-analysis of five studies suggested that meat consumption might have a protective effect against cognitive disorders. However, the authors acknowledged the possibility of publication bias influencing this result.

One strength of this review lies in its detailed discussion of the inherent challenges in nutritional science, particularly when it comes to isolating diet-disease relationships. The authors highlighted substantial variability in study designs, with none of the included studies accounting for important factors such as cooking methods or meat sourcing, both of which can significantly affect meat's nutritional composition. This review stands as the first systematic effort to examine the specific relationship between meat consumption and cognitive health, but further research is needed to address these confounding variables and provide more conclusive evidence.

In a related study from 2019, the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study investigated the role of egg consumption in cognitive performance and dementia risk among men in eastern Finland. Eggs are rich in choline, particularly phosphatidylcholine, a nutrient believed to support cognitive function and potentially reduce the risk of cognitive decline. Among 2,497 participants, those meeting their recommended choline intake showed no signs of impaired cognitive performance or elevated dementia risk, while those with insufficient choline intake exhibited poorer cognitive performance and an increased risk of developing dementia.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, is a significant health concern as it increases the risk of frailty, falls, and reduced quality of life in older adults. A European LifeAge study that followed 629 middle-aged and older adults found that consuming more than one portion of meat per day offered protective benefits against the development of sarcopenia.

These findings were further supported by a systematic review, which concluded that a diet inclusive of meat provides the most effective protection against sarcopenia compared to plant-based diets. Meat's rich profile of high-quality protein and essential nutrients, such as heme-iron, zinc, and vitamin B12, is thought to contribute to its protective effect by supporting muscle maintenance and repair.

Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer

Nutritional recommendations are often based on observational studies, which carry a high risk of confounding causal inferences. To address this, a panel of 14 researchers conducted four systematic reviews to evaluate the health effects of unprocessed and processed red meat consumption and develop dietary guidelines for the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) Consortium.

The reviews examined the potential impact of red meat consumption on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes. After analyzing 12 randomized trials involving 54,000 participants, the panel found low to very low-certainty evidence that reducing unprocessed red meat intake may have little to no effect on major cardiometabolic outcomes, cancer mortality, or cancer incidence. A dose-response meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies with 1.4 million participants similarly showed low to very low-certainty evidence suggesting a minimal reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes and type 2 diabetes with decreased red meat intake. There were no statistically significant differences observed for all-cause mortality or cardiovascular events.

When it came to cancer outcomes, dose-response meta-analyses of 17 cohort studies with 2.2 million participants found low-certainty evidence suggesting a minimal reduction in lifetime cancer mortality associated with reduced red meat intake. However, no statistically significant associations were observed for the incidence of specific cancers, including breast, colorectal, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. A broader review of 70 cohort studies involving over 6 million participants provided similarly inconclusive evidence regarding adverse cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes.

Based on these findings, the researchers issued a recommendation for the public to continue including unprocessed red meat as part of a healthy diet, noting that this was a "weak recommendation" supported by low-certainty evidence.

The analysis was notable for its rigorous methodology, employing the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence. The panel included a diverse group of nutrition experts, methodologists, healthcare practitioners, and members of the public, minimizing conflicts of interest through a thorough prescreening process. Although a financial conflict of interest was disclosed in a correction issued a year later, the transparency of the review process added credibility to its findings.

Most importantly, this review underscores the need for higher-quality research with robust methodologies to better control for confounding factors before issuing sweeping dietary recommendations, such as advocating for meatless diets.

The Diet-Heart Hypothesis

A 2019 meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that low-fat diets aimed at reducing serum cholesterol do not significantly reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. Similarly, an epidemiological study of 42 European countries showed a negative correlation between animal product consumption and heart disease and a positive correlation between carbohydrate intake and heart disease. The PURE study, which followed 140,000 individuals across 18 countries, found that animal protein consumption was associated with a lower risk of mortality, while saturated fat intake was linked to a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and a 20% reduced risk of mortality. In contrast, the cohort with the highest carbohydrate intake demonstrated a 28% higher risk of mortality.

Further evidence from a 2015 meta-analysis concluded that “saturated fats are not associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, or type 2 diabetes,” whereas trans fats were linked to increased all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease mortality. The Zoe Harcombe meta-analysis of RCTs, which reviewed over 62,000 patients, also found no significant health benefits from interventions aimed at reducing dietary fat intake.

In 2016, Christopher Ramsden, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, unearthed unpublished raw data from a 40-year-old study stored in a basement. This previously unavailable data contradicted the prevailing hypothesis that vegetable oils are healthier than animal fats in terms of heart health. This discovery underscores the importance of publishing all raw data to avoid confusion, ensure scientific integrity, and prevent potentially flawed health recommendations from becoming widely accepted.

This emerging body of evidence challenges the validity of the diet-heart hypothesis, initially popularized by Dr. Ancel Keys in the 1950s. Keys’ Seven Countries Study suggested a strong correlation between dietary fat intake and heart disease, heavily influencing the 1977 dietary recommendations issued by the US Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. However, critics have noted methodological limitations in Keys’ work, including selective inclusion of countries that supported his hypothesis, while excluding others that did not.

To offer a nuanced perspective, it’s worth noting that Ancel Keys was a pioneering scientist whose work spurred decades of research into diet and cardiovascular health. While aspects of his conclusions are now contested, his contributions laid the foundation for the broader field of nutritional epidemiology. Today, researchers are investigating alternative hypotheses, including the possibility that omega-6 vegetable oils, particularly their oxidized linoleic acid content, may play a role in coronary heart disease.

Anemia

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis examining the impact of vegetarian and vegan diets on iron status in adults found that individuals following meatless diets are significantly more likely to have lower iron stores. This deficiency places them at an increased risk of developing anemia, a condition characterized by insufficient hemoglobin levels, which can lead to fatigue, weakness, and impaired cognitive function.

The risk of iron deficiency in these populations is largely attributed to the absence of heme iron, the most bioavailable form of dietary iron, which is found exclusively in animal products such as red meat, poultry, and fish. In contrast, plant-based diets rely on non-heme iron sources, which are less efficiently absorbed by the body. Factors such as phytates and oxalates, commonly found in plant-based foods, can further inhibit iron absorption.

Additionally, iron deficiency may have broader health implications. Some studies have suggested a potential link between low iron levels and an increased risk of chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, although further research is needed to clarify this association.

These findings underscore the importance of dietary planning for individuals on meatless diets to ensure adequate iron intake. Strategies such as consuming iron-fortified foods, pairing non-heme iron sources with vitamin C to enhance absorption, or considering supplementation can help mitigate the risk of iron deficiency and related health complications.

Bones and Teeth

The EPIC-Oxford study revealed that individuals following vegetarian and vegan diets face a significantly higher risk of total and site-specific bone fractures, including fractures of the hip, leg, and vertebrae, compared to those consuming meat. This increased fracture risk is largely attributed to lower bone mineral density (BMD) observed in vegetarians and vegans, which is thought to result from inadequate calcium intake—a key mineral for maintaining strong bones.

Calcium is most bioavailable in certain animal-derived foods, such as dairy and meat products. In plant-based diets, calcium absorption can be hindered by compounds like oxalates and phytates found in some vegetables and grains. Additionally, insufficient intake of other nutrients critical for bone health, such as vitamin D and protein, may exacerbate the risk of fractures among individuals on meatless diets.

Furthermore, research has indicated that vegan and vegetarian diets may be associated with an increased risk of dental erosion and poorer overall oral health. This association may stem from higher consumption of acidic foods, such as fruits and plant-based beverages, as well as a potential lack of fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin K2, which plays a role in dental and skeletal health.

These findings highlight the importance of carefully planning vegetarian and vegan diets to include adequate levels of calcium, vitamin D, and other nutrients essential for maintaining bone and dental health. Supplementation or fortified foods may also help bridge these nutritional gaps for individuals adhering to plant-based diets.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Research indicates that individuals with a clinical diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) often exhibit significantly lower serum levels of total carnitine, free carnitine, and acylcarnitine compared to healthy controls. These deficiencies in carnitine levels may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, a factor frequently implicated in the pathophysiology of CFS. Mitochondria are the energy-producing organelles within cells, and disruptions in their function can lead to profound fatigue and reduced cellular energy output, hallmarks of CFS.

Carnitine is a compound critical for transporting fatty acids into mitochondria, where they are metabolized to produce energy. The richest dietary sources of carnitine are animal-derived products, such as red meat, fish, poultry, and milk. While the body can synthesize carnitine endogenously from amino acids like lysine and methionine, dietary intake remains a vital contributor to maintaining optimal levels, particularly for individuals with higher metabolic demands or compromised carnitine synthesis.

Given the established link between carnitine deficiency and mitochondrial dysfunction, ensuring sufficient dietary carnitine intake through animal products may play a supportive role in managing symptoms of CFS. For individuals adhering to plant-based diets, supplementation of carnitine may be necessary to address potential deficiencies and support mitochondrial health.

IQ and Child Development

Extensive research has associated the absence of meat consumption with potential developmental challenges, particularly during critical periods such as childhood and adolescence. In 2016, the German Society for Nutrition explicitly stated that vegan diets are not recommended for children, pregnant or nursing women, and adolescents, basing their stance on a comprehensive review of the research. Following suit, the Royal Academy of Medicine in Belgium declared vegan diets “unsuitable” for children. Notably, Belgian authorities warned that parents enforcing a vegan diet on their children could face legal repercussions. Such measures highlight the concerns raised by pediatric health experts, emphasizing the potential risks of nutrient deficiencies.

Tragic cases underscore these concerns, such as the 2019 incident where a Florida couple was charged with murder after their 18-month-old toddler died of malnutrition resulting from a strict raw vegan diet. These cases, while extreme, underscore the critical importance of adequate nutrition during early development.

One of the most well-controlled studies examining the relationship between meat consumption, child development, and intelligence is the Kenyan School Children Study. In this intervention study, 555 children were divided into three groups, each receiving a different type of soup for lunch daily: one containing meat, one containing milk, and one containing oil. Over the study period, the children's school performance and intelligence levels were assessed before and after the intervention. The findings revealed that children who consumed meat soup significantly outperformed their peers on non-verbal reasoning tests and arithmetic assessments, suggesting a direct link between meat consumption and cognitive development.

These findings align with broader research suggesting that the inclusion of animal products in a child's diet provides essential nutrients—such as iron, zinc, vitamin B12, and high-quality protein—critical for brain development and optimal cognitive performance. While plant-based diets can be adapted to meet nutrient needs, achieving an equivalent nutritional profile often requires meticulous planning and supplementation, particularly for growing children.

Testosterone

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effects of high-protein diets on testosterone levels, finding that diets with protein intake ≥35% of total calories could lead to a decrease in resting total testosterone levels (approximately 5.23 nmol/L). The researchers suggested that such high-protein intake might exceed the urea cycle's capacity to convert nitrogen from amino acid catabolism into urea, potentially causing hyperammonemia and its toxic effects.

Interestingly, the meta-analysis also revealed that "medium-protein, low-carbohydrate" diets (<35% protein) were associated with the highest post-exercise testosterone levels, indicating a possible balance point between protein intake and hormonal health.

However, the study had methodological limitations that warrant further investigation. For instance, the analysis did not account for the types of protein consumed, such as processed versus unprocessed sources, which could influence the observed effects. Future research should explore these variables to determine whether the drop in resting testosterone levels is consistent across all protein sources or specific to certain types. Additionally, factors such as exercise regimens and individual metabolic differences may need to be incorporated into subsequent studies to refine our understanding of the relationship between protein intake and testosterone regulation.