The Church of Vegan vs. The Science of Meat

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” - Albert Einstein

Ellen White in 1864.

A Religious Awakening

Fuzzy vision fading to black, Ellen Gould Harmon White started to fall to the ground in the pew of her church in Portland, Maine in 1847. This small woman lay on the church’s dirt floor, unconscious and violently shaking, while the other congregants of the church stood motionless. Seizures were normal for her due to an accident at age 9 where a rock hit her head and left her facially disfigured. Today we would recognize this as a traumatic brain injury, but to Ellen, this began her religious conversion. You see, her seizures were not normal seizures - they were visions, messages from God.

Ellen is one of the founders of the world's 12th largest religions today, the Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) church. Her visions became the cornerstone of the religion’s teachings and heavily focused on meatless eating, because her visions had told her that the purity of this diet would bring one closer to God.

In 1855, as the church started to grow, four stout believers that the second coming of Christ was at hand had convinced Ellen and her husband to move the church and their religious publishing business to Battle Creek, Michigan. A child of one of those four adherents had dropped out of school as a sickly young boy and began working at his father’s broom factory. Ellen took a liking to him and hired this timid 12-year-old boy as the lead typist for her publications. As her protégé, he quickly rose from typist to printer's devil, eventually doing proofreading and editorial work. That young boy’s name was John Harvey Kellogg.

Kellogg, famous today for his namesake cereal brand, was enamored by the teaching of the church. He believed so heavily in their ideas on health, chastity, and purity that he eventually trained to become a medical doctor at the University Medical School in Ann Arbor, Michigan and then the New York University Medical College at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, in order to help promote his beliefs through medicine. He graduated in 1875.

John Harvey Kellogg

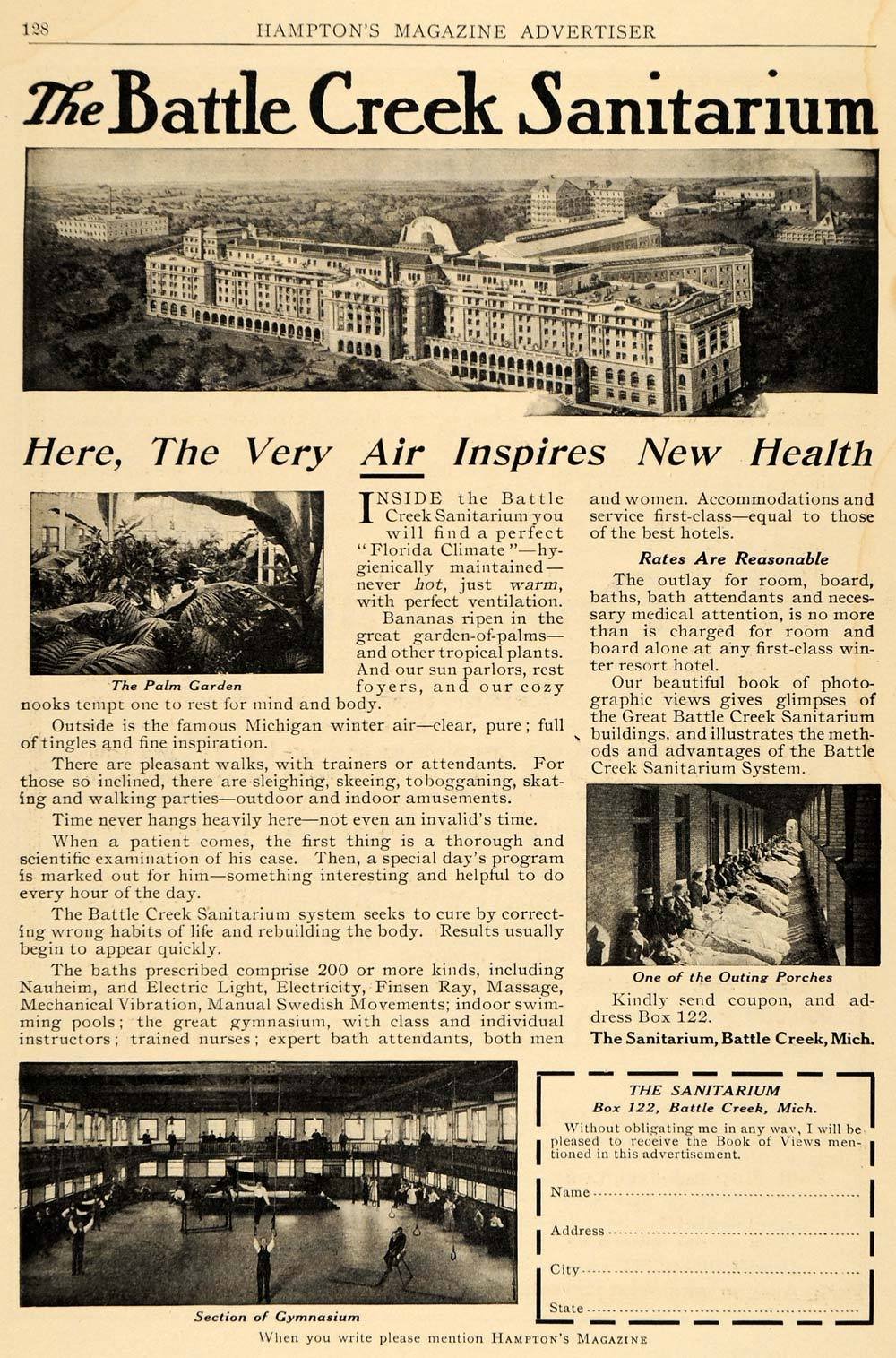

Upon returning to Battle Creek, Kellogg opened the Battle Creek Sanitorium with the help of the church and became the chief medical officer of the first Adventist Hospital.

Because of his religious beliefs, Dr. Kellogg was never comfortable about the idea of sex. He never consummated his marriage, choosing to adopt all of his children. He also believed that masturbation was a moral sin. These two ideas led to the development of what later became known as “Kellogg’s Cures,” which he was famous for at the time. The goal of the ‘cures' was ultimately to advance the teachings of the Adventist church, but patients weren’t necessarily looking for God when they sought out the help of this renowned doctor, they were looking for real medical help.

At his Sanitarium, Kellogg brutalized young boys that masturbated by punishing them with circumcision. In his book, Plain Facts for Old and Young, he wrote:

“A remedy for masturbation which is almost always successful in small boys is circumcision, especially when there is any degree of phimosis. The operation should be performed by a surgeon without administering anesthetic, as the pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if it be connected with the idea of punishment.”

A 1910 advertisement for the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

He also practiced a procedure in which he would pour carbonic acid on young girl’s clitorises in order to make them less sexually promiscuous later in life. Other treatments included 15-quart enemas and electrical shock currents applied to the eyeballs. Kellogg practiced what he preached and circumcised himself at age 37 without an anesthetic. In order to prevent his patients from this immoral “solitary vice", as he saw it, Kellogg advocated tying their hands, covering their genitals with patented chastity cages and even electric shock therapy, which was regularly used at the Sanitarium.

However, the crown jewel in Kellogg’s medical arsenal was diet. He rightly believed that diet could have a huge impact on one’s health. But his ultimate goal was not vitality, but rather he was seeking a diet that would make an adult have no sexual desire or libido.

Kellogg created a breakfast meal consisting of oatmeal and cornmeal baked into biscuits and then ground into tiny pieces, which he believed would heal the patient’s intestines and cure them of any sexual desires. He called it “granula,” but after a lawsuit had to settle on spelling it “granola.” It was his brother, Will Keith Kellogg, who worked at the sanatorium and lived in his brother’s shadow who had the genius idea to pour milk onto the granola to make it easier for the patients to eat.

One of Kellog’s patients at the sanatorium was none other than C.W. Post, who stole Kellogg’s cereal idea to create what would eventually become one of America’s largest food corporations: Post Consumer Brands. Seeing a business opportunity, John’s brother Will took the Kellogg name and left to begin producing Kellogg’s cereal at scale. Both of these men were unknowingly dispersing the tenets of the Seventh Day Adventist church all across the American breakfast table. The competition between these two men would eventually help to usher in the industrial food revolution of the 20th century.

But Kellogg wasn’t interested in big business and after a long lawsuit which severed his relationship with his brother, he sought to continue his work in medicine. In 1906, together with Irving Fisher and Charles Davenport, he founded a segregationist organization called the Race Betterment Foundation in order to further his religious work. The mission of this organization was eugenics. Kellogg believed that immigrants, non-whites, and mentally unstable individuals would damage the American gene pool. Working closely with the Michigan Board of Health, Kellogg created a piece of legislature that would go on to sterilize at least 3,800 “moral degenerates, sexual deviants, epileptics, the feebleminded or insane,” against their will.

A physical-fitness class at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, ca. 1890s. Director John Harvey Kellogg saw outdoor exercise, particularly in cold weather, as fundamental to health. Image from the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library.

While Kellogg was definitely one of the church’s most devout and notable conduits of influence, Ellen didn’t keep all of her eggs in one basket. The SDA church sought to promote their meatless diet and to influence health through any means necessary. They eventually built 198 sanitariums across the country, and created medical colleges in order to train their doctors. In 1917, the church also founded the American Dietetic Association to train dieticians how to properly teach their diet in order to promote chastity and purity. That same organization would eventually become the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, which describes itself today as “the world’s largest organization of food and nutrition professionals... shaping the public’s food choices.” In a paper entitled ‘The Global Influence of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church on Diet,’ the church freely admits that they “established hundreds of hospitals, colleges, and secondary schools and tens of thousands of churches around the world, all promoting a vegetarian diet.” The church most notably founded Loma Linda University, the Sanitarium Food Company, and what is known today as Loma Linda Foods.

Loma Linda University has trained thousands of doctors, nutritionists, dieticians, and research scientists over the last century. The university has sponsored and funded hundreds of “research studies” on meatless diets, making it hard to find a corner of nutritional science or research with a positive finding on these diets that hasn’t been touched by SDA. The SoyInfo Center even weighs in by saying that “no other organization or group of people has played a more important role than Seventh-day Adventists in introducing soyfoods, vegetarianism, meat alternatives, wheat gluten, dietary fiber or peanut butter to the Western world.”

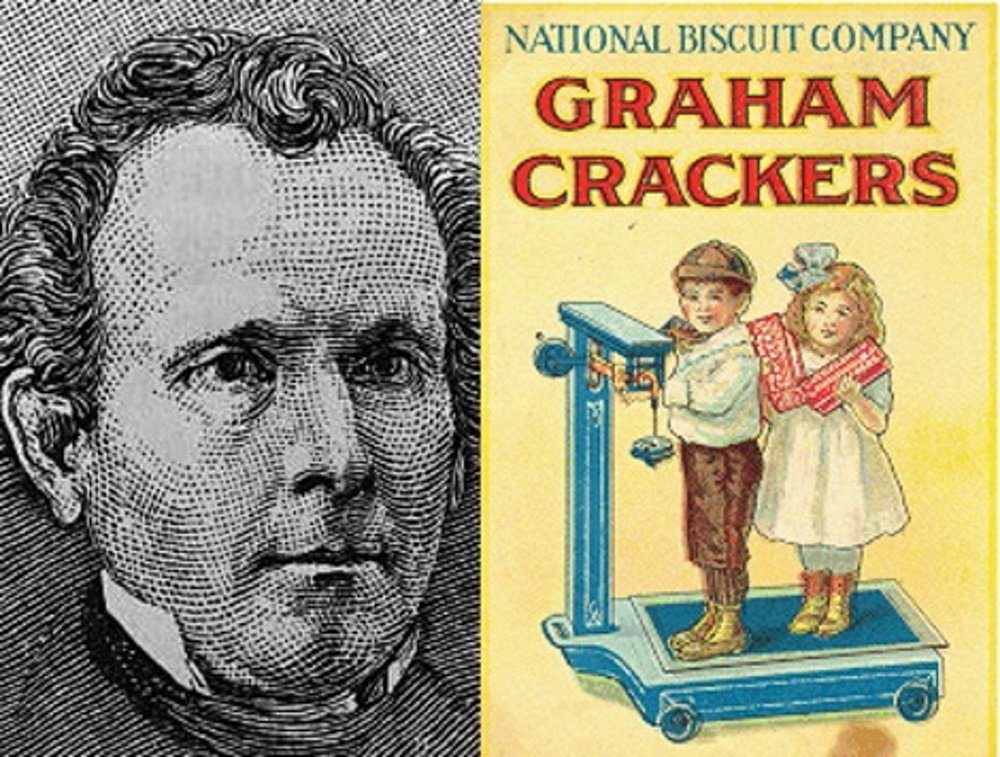

Rev. Sylvestor Graham and his famous Graham Crackers.

None of this had been happening in a vacuum though. The entire temperance movement in America during the 19th and early 20th centuries was largely due to the influence of religious theology on health. Temperance believers advocated for abstinence, no alcohol and oftentimes no meat. Another major proponent of temperance during the 1800’s was Rev. Sylvestor Graham, though he arguably didn’t have as much influence as Ellen and SDA. Graham, who later became the namesake of Graham Crackers, became heavily influenced by a book called Treatise on Physiology by a French physician named François-Joseph-Victor-Broussais. Published in 1826, Broussais wrote extensively in this book about the foods that people ate and how they have a massive impact on one’s health. He was, of course, right in his overall hypothesis. However, Graham filtered this idea through his religious indoctrination and arbitrarily decided that people should only eat plants because, he argued, that’s what Adam and Eve must have eaten in the Garden of Eden. His nutritional religion, known at the time as “Grahamism” spread like wildfire in the American northeast; his followers quickly developed and sold Graham flour, Graham bread, and eventually Graham crackers. Graham’s work also later heavily influenced Dr. Kellogg, as they both believed that this meatless diet would prevent children from having impure thoughts and in turn, stop all masturbation. In 1850, Graham co-founded The American Vegetarian Society in New York City, whose publication, now called The Vegetarian, is still published quarterly today. Graham died while receiving an opium enema at age 57. Still a controversial debate, historian Stephen Nissenbaum believes that Graham died "after violating his own strictures by taking liquor and meat in a last desperate attempt to recover his health."

However, the modern term “vegan” was originally coined by a British woodworker-turned-animal rights activist named Donald Watson in 1944. Watson was a member of the sister British puritanical organization to the American Vegetarian Society. But in 1944 something unique happened. 40% of all of the cows in the United Kingdom became infected with tuberculosis. Watson decided that in order to prevent the spread of disease, people should stop consuming dairy and eggs altogether. Of course, this diet would need a new name and thus “vegan” was born. After a few months, he had to issue a correction on the pronunciation, as most Brits began to refer to this diet as “veejan,” but nonetheless, the name eventually stuck.

Interestingly, when you begin to examine all accounts of meatless or vegetarian diets throughout history, it’s very difficult to find a culture that made this choice void of some type of religious, moral, or idealogical thinking. One of the earliest accounts of meatless eating was in ancient India, specifically those practicing Jainism — traditionally known as Jain Dharma. The idea was based on a moral code of ahimsa, or non-violence towards all living things. A quick fast forward throughout recorded history: during the Christianization of the Roman Empire in late antiquity monks banned the consumption of meat for ascetic reasons (based on abstinence and purity), Chinese Buddhism and Taoism required that monks ate a egg free and vegetarian diet, in the Vedic period of Hinduism, the Manusmriti law book states that abstinence from meat would “bring great rewards,” and so on...

So, how did this quasi-religious diet, created to promote chastity and purity, become the self-proclaimed diet of hipsters, hippies, and new age radicals in America during the 1970’s? After all, meat consumption in Western culture had risen dramatically between 1900 and 1960 due to transportation and refrigeration becoming easier (of which we can thank Clarence Birdseye). What changed?

In 1971, a woman named Frances Moore Lappé published a book called Diet for a Small Planet. Lappé had recently dropped out of U.C. Berkeley to pursue her own research on world hunger solutions. For Lappé, it was a question of math, not nutrition, arguing that we could completely end hunger if everyone on the planet ate a grain-based diet and ditched meat. Her work was ultimately a critique on the growing industrial food complex and not focused on optimal nutrition for individual health. Still, Diet for a Small Planet became her anti-hunger manifesto. Though Lappé’s entire focus was truly political, she single-handedly popularized the idea that plant-based diets were good for the planet. Her influence is still greatly impacting us today, as she is still giving keynote addresses about the impact of our diet on the environment all around the world. Simultaneously, an Australian ethics professor named Peter Singer wrote Animal Liberation, which was the first scholarly, philosophical argument against eating meat for moral reasons (PETA helped to popularize this book by printing free copies for new members). There are, of course, philosophical arguments against eating meat that span back to the ancient Greeks and Hindus, but Singer’s book launched a modern animal rights crusade that has become a global movement. Michael Pollan even once wrote that “Animal Liberation is one of those rare books that demand that you either defend the way you live or change it.”

By combining the pure-health ideological groundwork laid by religious institutions, like SDA, over the previous century with a “religion-like” ethical and moral academic argument that veganism was better for our planet, meatless America had hit what they viewed as a homerun. The 1970’s counterculture saw this diet as another tool that could be implemented to create “social change.” If big food was considered part of the establishment, then this diet was an anti-establishment protest. Suddenly, vegetarian and vegan communes began popping up all around the country; notably The Farm in Tennessee which was founded by a group of hippies from San Francisco. The Farm quickly set up a publishing company under the same name and began promoting meatless, soy-based recipes to its readers. Progressive Adventists at the time undoubtedly saw this as a baptism of sorts, as they witnessed ten new vegan societies being formed in Texas alone. Their ideas on purity were catching on and their “research studies” from Loma Lima University were being cited in these academic papers. In 1975, the New York Times even ran a headline titled, “Vegetarianism: Growing Way of Life, Especially Among the Young,” where staff writer Judy Klemesrud explicitly ties the knot between Lappé’s ideology and the Loma Linda research studies. Now that the meatless eaters had captured a wide audience, they only needed to push for a consensus in the medical community in order to drive their new-found diet home for good.

Their prayers were answered. In 1983, Dr. John McDougall began publishing a series of books to promote his hypothesis of how a vegan diet might treat all major illnesses. Dr. McDougall had experienced a sudden stroke at age 18, which perplexed all of his attending doctors at the time. Feeling let down by his medical care, he decided to pursue medicine and eventually attributed his early brain damage to “eggs, double-cheese pizzas and hot dogs.” He believed that a strictly vegan diet would essentially cure all modern chronic diseases. His work, of course, caught the attention of SDA and in 1986 he was invited by the church to run the “McDougall Program” as their lifestyle residential program at St. Helena Hospital in Napa Valley. I should note, however, that Dr. McDougall is not a member of the Adventist church, but nonetheless, the church extensively promoted him.

Since that time, there has been a constant onslaught of propaganda encouraging people to become vegan or to consume a ‘plant-based diet’ for their health and the health of the planet. As such, it’s important to understand how conversations about climate change have helped to bring vegan and vegetarian diets to a new level of popularity.

John Wesley preaching in Aldersgate, London (May, 1738).

Anti-Meat Investing

The mid and late 1990’s saw a substantial rise in “socially responsible investing” (SRI). Funnily enough, the concept of “socially responsible investing” originated as a religious one. The founder of the Methodist movement, John Wesley, had asked his followers in the 1700’s to avoid partnering or investing with those who earned their money through alcohol, tobacco, weapons, or gambling (sometimes referred to as sin stocks). The idea was that by aligning the way you spent your money and who you did business with, your religious or moral views could have a stronger impact on the world around you. This was also practiced for hundreds of years in Islamic finance, where ‘Shariah-complient investing’ banned investments related to activities prohibited by Islam.

But many investors in the late 1990’s also saw the rise of climate change as a significant business risk, so SRI pivoted to environmentally sustainable investments which is rated by Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG’s), and guided by what the United Nations would eventually deem their Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s). What made this investment movement different, is that a generation of people who grew up during the 1970’s counterculture, suddenly had money. They wanted their investments to align with what they believed and looked to the U.N. to help guide that strategy.

In 2006, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization published a report entitled “Livestock’s Long Shadow.” This report received massive international attention and claimed that livestock was producing more than 18% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Their shocking conclusion: livestock did more damage to the climate than all transportation emissions combined. The only problem is that their science was flawed, as was pointed out by UC Davis animal scientist Frank Mitloehner Ph.D.. The report’s senior author, Henning Steinfeld, even issued a correction, saying that the report “measures direct emissions from transport against both direct and indirect emissions from livestock,” which is referred to as a full ‘Life Cycle Analysis.’ Essentially, they had scrutinized every aspect of livestock, from feed, to fertilizer, to transportation, to belching, and land conversions, but the report did not equally scrutinize transportation. They did not include manufacturing, assembly, or road maintenance, and instead only examined a single variable: exhaust. The study also did not stipulate the difference between farms that utilized regenerative farming practices and large industrial livestock farms. All of these methodological errors skewed the numbers dramatically against the meat industry as a whole. But Steinfeld’s retraction didn’t matter. The damage was done and the investment into plant-based diets had already begun to pour in like never before.

Suddenly, Loma Linda Foods had competition in the marketplace. Impossible Foods, Beyond Burger, and other plant-based companies began popping up everywhere. And for the first time ever, there was an opportunity to own intellectual property in the meat market. These new companies had capital, leverage, a patented product, and most importantly, a moral story to sell: you can save your planet and better your health by purchasing our products.

Investors in these companies, particularly major family offices who were now heavily invested in plant-based foods, sought to create documentaries, books, and other forms of media to help sell their diet to the world. And I don’t believe they were doing so nefariously. In the same way that the Seventh Day Adventist church has believed that they were doing their part to help the world, these investors wanted to make a difference.

The Science of Meat

In May 2020, the New York Times published an opinion piece by Jonathan Safran Foer titled “The End of Meat is Here,” emphatically proclaiming that the historical moment had arrived to give up meat-eating for good, but many scientists, medical doctors, researchers, dietitians, and nutritionists couldn’t disagree more.

Figure 5. from Meat and Nicotinamide: A Causal Role in Human Evolution, History, and Demographics

Steady rise of meat/nicotinamide in surviving hominids until the Neanderthals. Homo sapiens survived, but only just, and then we subjected ourselves to large meat variances with demographic consequences.

It’s no secret that meat has been the cornerstone of the human diet for most of evolution. Archaeological and palaeo-ontological research indicates that at least 3 million years ago, hominids increased meat consumption and thus developed the brain capacity to fabricate stone tools, as well as the bodies necessary for foraging and hunting. Often referred to as the ‘cradle of mankind’ this evolutionary leap occurred in the Rift Valley in East Africa, where hunting and foraging required a clever approach due to the high level of predator danger. Through continued evolutionary changes, hominids eventually developed tools for hunting, butchery, and cooking, which saved in time and effort spent chewing and digesting. This ambitious transition from prey to predator also required advanced social cognitive skills, as the division of labor made the social group as a whole more successful. This included the cooperation and strategy to hunt in groups, but also the prosocial and altruistic skills necessary to share the food with the whole group. All of these components necessitated the development of very big and impressive brains, which have extraordinary energy requirements to sustain. These energy requirements are even more staggering during youth development, in which roughly 90% of the basal metabolic rate is needed to fuel a growing brain. Simply put, this development would not be possible without animal-derived foods in their diet.

Professor Robert Pickard, Emeritus Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Cardiff, who sits on the Meat Advisory Panel (MAP), which is a group of doctors, researchers, and nutritionists who provide recommendations on the role of meat in a healthy diet, elaborated on why meat is so important for the brain:

“This is because red meat is an excellent source of energy – although the brain is just two per cent of our body weight, it uses about 20 per cent of our energy intake. Red meat from grass-fed cattle is also a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, including a type of long-chain Omega-3 unsaturated fat called DHA which is vital for brain development. There are two active forms of long-chain Omega-3s in the body, EPA and DHA. DHA is the most abundant Omega-3 fatty acid in the brain and low levels of DHA can adversely affect various aspects of cognitive function and mental health, especially in young people and children.”

Dietary composition can be consistently linked to nearly every major turning point throughout human evolution, with meat playing a central and pivotal role in reducing digestive costs, while optimizing nutritional input. If you fast forward throughout recorded history, you will find countless examples of societies thriving when eating meat-centric diets and collapsing when meat is noticeably lacking.

Cultures That Thrived on Meat

Inuit children eating raw caribou.

The Inuits

Interestingly, at the turn of the century, while Kellogg was trying to improve his meatless diet in Battle Creek, a Harvard-trained anthropologist named Vilhjalmur Stefansson was living with Inuit tribes in the arctic, eating and trying to understand their diet, which consisted of almost exclusively caribou, salmon, and eggs. Stefansson was fascinated because the inuits did not follow anything close to the diet being promoted in the modern world, but as he wrote, they were “the healthiest people he had ever seen.” He observed no signs of disease and noted that the Inuits prized the fattiest parts of meat as the healthiest, which was the opposite of dietary thinking at the time. Stefansson and one of his colleagues then tried to eat a meat-only carnivore diet for an entire year to see what would happen. They realized that they felt the best while eating the fattiest meats and brains. By the end of their year-long experiment, a committee of scientists examined each of them thoroughly and could find nothing wrong with their health. Arguably, there is no other scientist alive today whose nutrition-investigative experimental designs had been so well controlled and at such a large scale as Stefansson.

The Masai and Samburu of Kenya

A similar line of inquiry occurred in the 1960’s when doctor and professor of biochemistry, George Mann, began studying the Masai people in Kenya. Notably, the Masai consumed a diet of only milk, blood, and meat — choosing to feed all of their vegetable crops to their animals instead. Through extensive testing, Mann observed that the Masai people had no evidence of high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, or the other chronic illnesses that were already prevalent throughout the Western world. The exact same results were observed in the Samburu tribe in Northern Kenya, who ate basically the same diet as the Masai.

The Native American Tribes

The physician and anthropologist, Aleš Hrdlička, extensively studied the Native Americans of the Southwest between 1898-1905, noting that their diet consisted almost entirely of meat, mainly buffalo. In his 460-page report for the Smithsonian Institute, Hrdlička observed that Native Americans lived incredibly healthy and long lives, with one of the highest percentages of centenarians in recorded history (40 times more centenarians than in typical Western culture at the same time). He was also struck by the lack of diseases plaguing Native Americans, noting that “malignant diseases, if they exist at all… must be extremely rare.”

The Mongols

The Mongolian Army, founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, conquered large spans of Europe and Asia, covering nearly 12 million square miles of land. Notably, their nomadic life forced them to eat a diet of mainly diary products from their herds of goat, sheep, oxen, camels, and yaks traveling with them. One of their most popular drinks was called Kumis, which was typically made from fermented milk churned in large leather bags. Fueled only by animal products, the Mongolian Army became famous warriors, known for their speed, strength, and agility.

Meatless Societal Collapse

The Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange references the mass exchange of diseases, ideas, food, and populations between the “New World” and the “Old World” after Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas in 1492. As new diseases were introduced to the native populations, many of their people died, particularly in tribes that had a low-meat/high-maize diet, which may have already left their health at some risk. Other scholars have suggested that the ancient Mayan civilizations collapsed specifically due to their Maize-centric diet. Likewise, the subsequent introduction of maize to Europe was directly responsible for outbreaks of Pellagra (caused by a vitamin B deficiency) in Spain and Italy in poorer communities that could not afford meat.

Easter Island

Anthropologically, Easter Island provides a perfect microcosm case-study of the effects of no meat in a population’s diet. As islands cannot support big game, Easter islanders’ eventually resorted to eating rats and fighting with other omnivores for seagull eggs. The lack of big game eventually lead to a complete population collapse on the island.

Ireland

Researchers at the University of Birmingham have noted through their anthropological research that “high meat intake correlates with moderate fertility, high intelligence, good health, and longevity with consequent population stability, whereas low meat/high cereal intake (short of starvation) correlates with high fertility, disease, and population booms and busts.” This is particularly evident in Ireland during the famine of the mid-19th century. As the Irish population was too reliant on potato and had subsequently low meat intake, they were equally plagued with high population growth and later collapse.

Animal Protein vs. Plant Protein

Protein is a macronutrient found in animal and plant-based foods that is made up of amino acids, which facilitates multiple essential functions in the body, including muscle and tissue repair, hormone regulation, facilitation of enzymatic processes, and transportation and storage of molecules such as oxygen. Amino acids and proteins are essentially the building blocks of life. Both plant and animal proteins contain varying amounts of amino acids, making some complete sources and some incomplete sources of protein. A food source is considered to be a complete protein when it contains all nine essential amino acids (isoleucine, histidine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine), and incomplete if any of these nine are missing. The protein digestibility corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) has been adopted throughout nutritional research as the most accepted and widely used method for measuring how complete a protein source may be. Proteins from animal sources (e.g., eggs, milk, meat, fish, and poultry) are the highest quality rating of protein source in a food (see the 5th column in Table 1 below).

PDCAAS-adjusted P/E ratios of animal and plant food sources and diets

If your body is not getting enough protein through your diet, it will begin to break down your own muscle and tissue to get the protein it needs. The current recommended daily allowance (RDA) of protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of bodyweight according to the US Dietary Guidelines. However, research has since indicated that this RDA is the minimum amount of necessary protein to avoid loss of muscle mass, not the optimal amount. For example, a person that weighs 165 pounds (75 kilograms) would need to eat a minimum of 60 grams of high quality protein (complete sources) per day just to prevent loss of muscle mass. For context, a 6 ounce steak contains roughly 42 grams of high quality protein.

However, this RDA for protein is based on a healthy adult with “minimal physical activity” and should be adjusted for individuals based on age, weight, height, and physical output. Researchers have also suggested that functional needs, such as support of spermatogenesis, fetal survival and growth, blood circulation, resistance to infectious disease, as well as skeletal muscle mass and health should all be taken into account when calculating the RDA for protein. When all of these variables are taken into account, the RDA could be more in the range of 1.0, 1.3, and 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day as the recommendation for adult individuals with minimal, moderate, and intense physical activity, respectively. Yet, children and infants have even greater protein requirements to fuel their exponential growth, as do older adults experiencing age-related muscle loss.

Infographic created by Diana Rodgers RD for The Sacred Cow Project.

So, let’s go back to our example for a second: an active and healthy 165 pound (75 kilogram) male, may actually need roughly 120 grams of protein per day. This is assuming that all 120 grams of protein are high quality complete sources of protein that contain all of the essential amino acids. That would be roughly three 6 ounce steaks per day, just to meet the protein requirements needed in order to maintain muscle mass. However, if your protein sources are incomplete sources, which all plants are, this calculation becomes incredibly more complex in order to hit both the appropriate protein RDA for your body weight, as well as a complete profile of all of the necessary amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. As an example, in order to obtain that RDA from broccoli alone, you would need to consume roughly 120 ounces of broccoli (that’s more than 46 cups of broccoli), and you would still be lacking in 3/9 essential amino acids (isoleucine, leucine and methionine). Registered dietician, Diana Rodgers, compared the protein value of a 4 ounce steak with kidney beans (which vegans and vegetarians commonly consider to be a good source of protein) and found that in order to get the same amount of protein as the steak, you would need to consume 12 ounces of kidney beans, plus a cup of rice, which amounts to roughly 638 calories and 122 grams of carbohydrates — and even then, you would still be lacking in other vitamins and minerals.

Because not only is meat the most complete source of amino acids, but red meat in particular also provides the most bioavailable source of heme-iron, which is incidentally, the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide. Meat is also a considerable source of bioavailable vitamin B12 (cobalamin), of which meatless eaters are at a significant risk of being deficient. Remarkably, just 3 ounces of red meat contains more than half of the RDA for selenium and niacin, as well as nearly half of the RDA for zinc, further emphasizing it’s rich nutrient density. A selection of micronutrient claims for beef, lamb, pork, venison, and calf liver are presented below.

Table 1. from The role of red meat in the diet: nutrition and health benefits

Selected micronutrients in meats related to nutrition claims classification. Data from McCance and Widdowson's Composition of Food ND, no data; Beef, beef average, trimmed lean, raw; Lamb, lamb, average, trimmed lean, raw; Pork, pork, trimmed lean, raw; Venison, venison, raw; Calf liver, liver, calf, raw.

Furthermore, the consumption of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFA), namely eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), is associated with many health benefits, notably in fetal development, for cardiovascular health, and for brain health — with particular associations relating to Alzheimer’s disease. There are notable differences in omega-3 levels in individuals with different diets, particularly when comparing diets containing meats with vegan or vegetarian diets, as can be seen in a 2005 British cross-sectional study. The data from this study comparing the amount of EPA, DPA, and DHA in different diets can be seen here (see Table 2 in the study for a full chart):

EPA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 0.72 / Vegetarians: 0.52 / Vegans: 0.34

DPA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 0.81 / Vegetarians: 0.76 / Vegans: 0.72

DHA levels (mg/L): Omnivores: 1.69 / Vegetarians: 1.16 / Vegans: 0.7

Clearly, the omnivores have better levels of EPA, DPA, and DHA, of which vegans and vegetarians are not converting from alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) efficiently (this conversion process is outlined in the diagram below). These findings can be confirmed in other studies of Austrian, Dutch, Australian, Finnish, Chinese, and US adults. To be clear, these findings do not suggest that it is impossible to get the appropriate amounts of omega-3’s from vegan or vegetarian diets, but rather, that it is difficult and complex to adequately supplement and that including animal products in one’s diet provides a natural and efficient way to maintain optimal levels.

An adapted diagram from Essential fatty acids: biochemistry, physiology and pathology (Adapted by Chris Kresser, M.S., L.Ac)

The Clinical Benefits & Risks Related to Meat

Dietary studies are notoriously difficult to assess due to many the confounding variables at play. Individuals have different genetics, cook their food differently, source their food differently, use different ingredients, have different light exposure, take different medications, have different pre-existing conditions, live in different areas, have different socioeconomic advantages, have access to different medical care, have different physical activity, and so on. It’s very hard to tease out whether any changes in risk or development of diseases are due to one specific ingredient in someone’s diet. It’s also important to be aware that there are obviously different types of meat, that meat can be processed or unprocessed, as well as grass-fed or grain-fed — all of which will affect its nutritional composition and most of which is rarely controlled for in nutritional studies. Finally, one of the biggests problems with observational studies on meat is what is referred to as the “healthy-user bias,” in which individuals participating in the study who engage in one behavior that they believe to be healthy are more likely to engage in other behaviors that are healthy. Since meat has been given such a bad reputation for the past 40 years, it is very difficult to find a cohort of participants that consume meat regularly and engage in other healthy behaviors (e.g., physically active, care about the sourcing of their food or a balanced diet, don’t smoke, etc.).

Having said all of that, here is evidence that I believe best controls for as many confounding variables as possible:

Depression & Anxiety

As red meat is a rich source of vitamins and minerals, it is believed to play a protective role in common mental disorders. Researchers in the field of nutritional psychiatry have found that women who consume either less or more than the recommended intake of red meat were significantly more likely to develop clinical depression, mood, or anxiety disorders. Lead researcher and associate professor from Deakin’s Barwon Psychiatric Research Unit, Felice Jacka, Ph.D. elaborated on the importance of red meat for optimal brain health:

“We had originally thought that red meat might not be good for mental health, as studies from other countries had found red meat consumption to be associated with physical health risks, but it turns out that it actually may be quite important…

When we looked at women consuming less than the recommended amount of red meat in our study, we found that they were twice as likely to have a diagnosed depressive or anxiety disorder as those consuming the recommended amount.

Even when we took into account the overall healthiness of the women’s diets, as well as other factors such as their socioeconomic status, physical activity levels, smoking, weight and age, the relationship between low red meat intake and mental health remained. Interestingly, there was no relationship between other forms of protein, such as chicken, pork, fish or plant-based proteins, and mental health.”

Theses findings were replicated in a prospective study of 10,094 Spanish individuals enrolled in the SUN Project, in which researchers also observed that a lack of meat in the participant’s diet led to an increased risk of depression. Conversely, other research has shown that vegetarians are much more likely to experience depressive symptoms, which was further confirmed in a large 2018 cohort study of 90,380 participants.

Multiple Sclerosis

In 2019, researchers began to examine the relationship between red meat and a clinical diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination (FCD), which most often presages a full diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS). After adjusting the data to control for history of infectious mononucleosis, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations (vitamin D3), smoking, race, education, body mass index and dietary misreporting, they still found that higher non-processed red meat consumption was associated with a reduced risk of FCD; a reduction of 19% per one standard deviation increase in non-processed red meat density. These researchers noted that red meat contains both VLCn3PUFA and vitamin D, which are known to play critical and protective roles in the central nervous system and of which a deficiency in either has been associated with the risk and/or progression of MS.

Neurodegernative Disorders

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis examining the association between meat consumption and cognitive function/risk of cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia looked at 29 different papers with very inconsistent findings. The majority of studies in the analysis showed no association between meat intake and risk of cognitive disorders. However, meta-analysis of five studies suggested that meat could actually have a protective benefit against cognitive disorders (although a potential publication bias was acknowledged). What I like most about this review is that the authors articulate the many challenges in establishing concrete associations in nutritional science. For example, there is vast heterogeneity in the study designs and none of the studies in the analysis took into account cooking methodology or sourcing of meat, which is noted in the review to impact its nutritional composition. To my knowledge, this is the first systematic review to specifically explore the association between meat consumption and cognitive function/risk of disease and future studies are needed to continue to isolate confounding variables that could impact the results.

However, in 2019, the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study tracked cognitive performance and risk of dementia for men in eastern Finland to assess the association with their egg intake. Why? Because eggs are rich in choline, specifically phosphatidylcholine, which is believed to help prevent cognitive decline. Of the 2,497 participants, the men that were reaching their total recommended choline intake had no impaired cognitive performance or associated risk of dementia, whereas the group lacking in choline had poorer cognitive performance and an increased risk of developing dementia.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and associated muscle weakness. A European LifeAge study followed 629 middle-aged and older adults and found that more than one portion per day of meat can be protective again developing sarcopenia. These findings were confirmed in a systematic review that found that a meat-inclusive diet provides the best protection against sarcopenia.

Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer

After noting that nutritional recommendations are primarily based on observational studies, which are considered high risk for confounding casual inferences, a panel of 14 researchers performed four systematic reviews to assess the health effects associated with red meat and processed meat consumption in order to recommend a set of dietary guidelines for the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) Consortium. All four systematic reviews intended to assess the possible impact of unprocessed red meat and processed meat consumption on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes.

After reviewing 12 unique randomized trials, enrolling 54,000 participants, the review found low- to very low-certainty evidence that diets lower in unprocessed red meat may have little or no effect on the risk for major cardiometabolic outcomes and cancer mortality or incidence. A dose-response meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies with 1.4 million participants also provided low- to very low-certainty evidence that decreasing unprocessed red meat intake may result in a very small reduction in the risk for major cardiovascular outcomes and type 2 diabetes, with no statistically significant differences for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events. Dose–response meta-analysis results from 17 cohorts with 2.2 million participants also found low-certainty evidence that decreasing unprocessed red meat intake may result in a very small reduction of overall lifetime cancer mortality, with no statistically significant differences for prostate cancer mortality and the incidence of overall, breast, colorectal, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. An additional 70 cohort studies with just over 6 million participants similarly provided mostly uncertain evidence for the risk for adverse cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes.

As such, the researchers made a recommendation that the public continue consuming unprocessed red meat as an essential component of a healthy diet (however this was noted as a weak recommendation with low-certainty evidence).

This analysis has several strengths, including methodology, a GRADE approach to address uncertainty of confounding evidence, and a diverse panel of nutrition experts, methodologists, health care practitioners, and members of the public. The panel minimized conflicts of interest by prescreening panel members for financial, intellectual, and personal conflicts of interest and providing a full account of potential competing interests — although one potential financial conflict of interest was disclosed in a correction issued a year later.

Most importantly however, this review process further highlights the need for more research, with better methodology to account for confounding inferences, before any drastic health recommendations, such as meatless diets, are made to the public.

The Diet-Heart Hypothesis

A 2019 meta-analysis of 22 RCT’s found that low-fat diets that reduce serum cholesterol do not reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. An additional epidemiological comparison of 42 European countries showed a negative correlation between animal products and heart disease and a positive correlation between carbohydrates and heart disease. Similarly, the PURE study examined a cohort of 140,000 individuals from 18 different countries and found that animal protein was associated with a lower risk of mortality and that saturated fat was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and a 20% lower risk of mortality. The group with the highest carbohydrate intake was associated with a 28% higher risk of mortality. Likewise, a 2015 meta-analysis concluded that “saturated fats are not associated with all cause mortality, CVD, CHD, ischemic stroke, or type 2 diabetes… [while] trans fats are associated with all cause mortality and CHD mortality,” and the Zoe Harcombe meta-analysis of RCT’s reviewed over 62,000 patients and found no significant changes in health from interventions lowering dietary fats. In a riveting turn of events in 2016, researcher Christopher Ramsden, of the National Institutes of Health, unearthed raw data from a 40-year-old study in a dusty basement that had never been published. The excavated data challenged the hypothesis that vegetable oils were healthier than animal fats in relation to heart health. This data discovery highlights how the failure of many scientists to publish all of their raw data can cause mass confusion, undermine scientific inquiry, and can potentially cause incorrect health recommendations to become socially accepted on a large scale.

This cited evidence completely disproves the diet-heart hypothesis as proposed by Dr. Ancel Keys in the 1950’s and based on his flawed Seven Countries Study, of which the 1977 US Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs based their dietary recommendations for Americans upon. Researchers have since proposed a hypothesis that omega-6 vegetable oils may actually be a key driver of coronary heart disease due to their content of oxidized linoleic acid.

Anemia

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effect of meatless diets on iron status in adults found that individuals that consume vegetarian and vegan diets are significantly more likely to have lower iron stores. These individuals are therefore at a higher risk of developing anemia or type 2 diabetes. An additional epidemiological comparison of 42 European countries showed a negative correlation between animal products and heart disease and a positive correlation between carbohydrates and heart disease.

Bones and Teeth

Results from the EPIC-Oxford study showed that vegetarian and vegan diets were both shown to significantly increase risks of either total or sit-specific bone fractures, particularly hip, leg, and vertebra fractures compared to meat eaters. Other analysis has shown that vegans and vegetarians have substantially lower levels of calcium due to the lack of meat in their diet, which is thought to be the cause of this increased risk of fracture. It has also been shown in research that vegan and vegetarian diets are associated with a much greater risk of dental erosion and poor overall oral hygiene.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Research has indicated that individuals who have been clinically diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome have statistically significantly lower serum total carnitine, free carnitine and acylcarnitine levels, which could cause mitochondrial dysfunction. Animal products like meat, fish, poultry, and milk are known to be the best sources carnitine.

IQ and Child Development

There has been extensive research associating the lack of meat consumption with impaired intelligence, especially during child development. In 2016, the German Society for Nutrition categorically stated that – for children, pregnant or nursing women, and adolescents – vegan diets are not recommended, which they based on a 2018 review of the research. After that, the Royal Academy of Medicine in Belgium also announced that a vegan diet was “unsuitable” for children, and that parents who force a vegan diet on their offspring in Belgium could even face criminal charges. Of course, there are notable cases of this happening, such as in 2019 when a Florida couple was charged with murder when their 18-month-old toddler died of malnutrition due to his strict raw vegan diet.

The most controlled study that I’m aware of involving meat, child development, and intelligence is the Kenyan school children study. In the study, 555 children were fed three different types of soup for lunch each day during school: one with meat, one with milk, and one with oil. Their school performance and intelligence levels were tested before and after the intervention period for comparison. The results: the children that consumed the soup with meat every day had a significant intellectual edge over the other two groups, outperforming on non-verbal reasoning tests and arithmetic assessments.

Testosterone

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that high-protein diets can cause a decrease in resting total testosterone (∼5.23 nmol/L). The researchers hypothesized that protein intakes ≥35% may outstrip the urea cycle's capacity to convert nitrogen derived from amino acid catabolism into urea, leading to hyperammonaemia and its subsequent toxic effects. Notably, this meta-analysis found that “medium-protein, low-carb” diets (<35% protein) resulted in the highest post-exercise testosterone levels. However, there are a few methodological problems with the analysis in this study that future research should consider, namely examining different “types” of protein as potential confounding variables (e.g., protein from processed meat vs. protein from unprocessed sources) and whether or not that still can trigger this drop in resting testosterone.

It’s Not the Cow, It’s the How

Natalie, a very curious cow, takes a break from converting grass into micronutrient-dense food in order to explore her visitor.

As we all know, many people make their food choices based on the health benefits of that food, but increasingly more and more people are including the environment in that equation. I think that’s great. We should be aware of how our food choices impact our biosphere because in the full cycle of life those choices will ultimately impact the nutritional value of our food. But I’m admittedly very perplexed by the particular focus on demonizing cows and the role they might play in climate change.

I want also to preface this section by stating very clearly that I am not a climate scientist or expert in this area of research, but I felt that I needed to at least address this topic to provide a fully rounded look at all of the factors weighing into why we consume meat today. I also approach this analysis with a biased belief that any proposed solution to the problem of climate change that is ‘anti-human’ is not a truly viable solution. And based on the abundant evidence outlining why meat has been so important for human health throughout evolution, I think that we should take a serious pause when the suggestion to remove meat from the human diet altogether is thrown about so easily.

Here is some research worth considering when thinking about animal-based agriculture and the climate:

In 2017, Professors Mary Beth Hall and Robin White published a paper modeling what would be the nutritional and greenhouse gas impact if the U.S. removed all animal products from our food supply.

Their model showed some significant trade offs. They estimated that a U.S. plant-only agricultural system would produce 23% more foods, but would simultaneously create substantial nutritional deficiencies in the population. But even more so, this dramatic shift would only reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2.6% — not a huge impact for making such a drastic change. The researchers concluded, “When animals are allowed to convert some energy-dense, micronutrient-poor crops (e.g., grains) into more micronutrient dense foods (meat, milk, and eggs), the food production system has enhanced capacity to meet the micronutrient requirements of the population.”

Animal scientist and lead reseacher at the Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research (CLEAR) center at UC Davis, Frank Mitloehner Ph.D., commented on this research, claiming that if American’s believe that eliminating meat from their diet will help to curb climate change, that they are “being deceived by misinformation that puts undue blame on animal agriculture.” He goes on to elaborate:

“Say for a moment, we did get rid of animal agriculture and lowered our greenhouse gas emissions by 3 percent; the gains would be fleeting. Biogenic methane from ruminants such as cattle is short-lived and referred to as a flow gas, meaning that as it is emitted to the atmosphere, some is also destroyed there. CO2 on the other hand, is a stock gas that builds up in the atmosphere. CO2 emitted today, is added to CO2 emitted yesterday and so on. Because so, it would only be a matter of time until CO2 emissions built up so much, that it would erase the warming reductions from eliminating animal protein.”

Instead, the CLEAR center at UC Davis suggests that methane from cattle can actually provide a climate solution.

Interestingly, the United Nations Food and Agriculture’s statistical database shows that direct GHG emissions from U.S. livestock have declined by 11.3% since 1961 due to improvements in U.S. farming practices, while the livestock production has more than doubled.

Additionally, a 2019 meta-analysis assessed the role of grazing lands (grass-fed cattle) and its subsequent effect on carbon sequestration by looking at soils in serval South American countries. Their results showed that the grazing practices used actually sequestered carbon into the soil, enough to potentially totally offset the local urban emissions. The researchers of this analysis concluded that “the potential of grazing lands to sequester and store carbon should be reconsidered in order to improve assessments in future GHG inventory reports.”

Another study from researchers at Michigan State University assessed the amount of carbon in the soil of two different sets of cattle: one in a traditional feedlot system and one where the cattle were free to graze on grass and rotated frequently between pastures. Their data showed that the feedlot system produced less total emissions, but the grazing cattle actually produced a net GHG sink. The authors end their analysis noting that their data contradicts the common mainstream narrative and recommended that grazing cattle be investigated as a tool to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Without animals to fertilize the soil with their excrement, our soil can also easily become depleted, causing many downstream effects in the nutrient value of our crops and therefore, our health. As grazing animals naturally fertilize the soil, the model mentioned above by Hall and White further noted that their removal from the food supply would have detrimental effects to our soil. And conversely, another study showed that the ammonia-based fertilizer needed to replace this excrement would emit 100 times more methane than the industry previously reported.

Even more so, a study in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation asserts that most agricultural soils in North America have lost 30% – 70% of their soil organic carbon (SOC), which has caused a decrease in food production and its nutrient value. The majority of this soil damage is caused by plowing fields for monocrop agriculture, as evidenced in the endless monocrop fields of corn and soybean in the midwest. Another paper asserts that the most devastating carbon emissions occurred in the 1930’s when a large portion of the Great Plains native grasslands that was previously grazed (mostly by North America’s previously massive bison population) was instead plowed for monocrops. Clearly, the problem is not the cow, but rather, it’s how we have industrialized our farming system.

The Moral Case for Meat

It’s very easy to find a philosophical argument against eating meat. And most of them are pretty convincing. After all, it’s very clear that animals are capable of feeling and have some level of consciousness. So at face value, it makes sense. But how coherent is this moral structure if we dig a little deeper?

As we’ve learned more about intelligence and consciousness, it’s very clear that this line of thinking is not consistent. A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences claims that most insects even have the neurological capacity “for the most basic aspect of consciousness: subjective experience.” Is the new trend of cricket protein therefore immoral? Plants also have a certain degree of intelligence and as we’ve learned recently, even ‘scream’ when being cut or harvested. Does that qualify as consciousness? Should we therefore also not eat plants? Shouldn’t this philosophical argument extend to all intelligent and conscious beings or does it only apply to some conscious beings?

I believe that any moral argument against eating meat is fundamental hypocritical, as humans need animal protein in our diets. I mean, even the Dalai Lama, who says vegetarianism is preferable, eats meat twice a week. As it seems to be a biological imperative, I think that it’s a worthwhile endeavor to explore the philosophical argument for eating meat. After all, what kind of moral structure would find it wrong to eat meat when we evolved precisely because of meat consumption and still biologically require it. Is it not also our moral imperative to bring our fullest potential into Being? And isn’t optimal nutrition a means to do that? If meat makes us healthier and more nourished versions of ourselves, then it is our moral duty to consume it.

His Holiness, the Dalai Lama

Taken from The Dalai Lama is a meat-eater?

Interestingly, the British philosopher Nick Zangwill published a paper entitled “Our Moral Duty to Eat Meat,” which I found rather compelling (you should give it a read).

In the paper, Zangwill argues that eating meat is not only a good thing, but that it is our moral duty because the existence of domesticated breeds of animals on farms depends on our practice of eating them. He cites an example of the many millions of sheep in New Zealand that would cease to exist if it were not for our practice of eating them. And the fate of those sheep, if left to the wild, is undoubtedly a far worse death than a humane slaughter could ever be. The practice of eating meat creates a solemn duty to the animal, as we have to care for it, provide it with a good life, and then slaughter it ethically — a duty and protection that ultimately would not exist if we weren’t invested in eventually eating that animal. But his argument gets even more fascinating when he actually agrees with Peter Singer’s claim that animal consciousness is the most important consideration, but Zangwill arrives at the opposite conclusion:

“Because some animals are conscious, they have interests and can flourish in a way that matters morally. But for many kinds of animals (cows, sheep, chickens), in order to exist and flourish in that way there must be a practice of eating them. Therefore, we should eat them.”

Or to put this another way, as English author Leslie Stephen once remarked, “The pig has a stronger interest than anyone in the demand for bacon.”

However, I would take Zangwill’s claims a step further. When Zangwill refers to our duty to the animal, he is referring to the relationship between us. And ideally, an ethical and meaningful relationship in nature is one that is symbiotic. I mean, is it not hubristic to make the claim that we, as humans, somehow exist outside of the circle of life? We too, will one day die and our bodies will decay and nourish the earth. As animals are indeed the ideal form of protein for humans, they are also the very thing that has fueled our brains in order to give us the intellectual capacity necessary to even consider their consciousness and wellbeing. So as we care for the animal, their final gift is to care for us by providing us with optimal nutrition, which in turn gives us better brains to continue to care for them. A gift that I personally give thanks for at every meal.

To be crystal clear, this is not a moral argument for animal cruelty. While suffering is ultimately an unavoidable facet of life, there is no reason that humans should cause wanton pain for animals. There are obviously means for ethical, regenerative farming and humane slaughter that should be used in every instance possible (also see Is Humane Slaughter Possible?). And as such, I believe that the truly moral calling for humans is to give animals a life worth living and then to cherish the nutritious gifts they leave for us upon their death.